China’s search for technological mastery will succeed because it is essentially replicating the actual history of the economics and policies that led the United States to technological dominance, rather than the ideological history of what many Americans believe lies behind their success For years, American policymakers and pundits have believed China’s search for technological mastery or supremacy is doomed to fail or at least be consigned forever to mediocrity and also-ran status. This belief lies behind the strategy, first put forward by the Donald Trump administration, and now followed by Joe Biden’s White House, to restrict or ban the transfer of crucial technologies, notably the most advanced semiconductors and their production methods. And yet, paradoxically, China is bound to succeed, despite the inevitable hiccups and setbacks, because it is essentially replicating the actual history of the economics and policies that led the United States to technological dominance, rather than the ideological history of what many Americans believe lies behind their success. They have applied their own ideological models to predict China’s supposedly “inevitable” failure, instead of using their own actual history of American technology and science, and economic policy, to analyse China’s development and acquisition of key technologies in the 21st century. This is perhaps not surprising. Rich, powerful and successful people usually tell a different story about how they get to where they are to what actually happened to them. It’s human nature. China’s Great Firewall It’s generally believed that free enterprise is the necessary and sufficient condition for hi-tech industries. This means: the free flow of information and talent; open market; no or minimal government intervention, also called deregulation; and intellectual property rights protection. It’s believed only the market can choose winners and eliminate the losers, and that any state attempt to choose “national champions” is bound to fail and to be wasteful. China’s so-called Great Firewall of the internet stands as both an actual barrier and a potent symbol that is antithetical to all those fundamental neoliberal assumptions, which, granted, are being increasingly challenged and even undermined, even among some US professional economists and historians. However, if you believe in all those assumptions, you of course will logically argue that China is bound to fail. But is it? Let’s consider the historical reference: the Great Wall of China. It has been alternately argued that it was built to resist foreign invaders, and/or to keep in the domestic population. Either way, it was too porous to be truly effective.

The Silicon Valley folklore is that of a lone maverick who has a great idea and pushes it to fruition, and in the process, creates a multibillion-dollar industry. That cannot be further from the assumption behind Japanese-Korean-Chinese state industrial policy, according to which innovation is a collective enterprise, not one of individual genius or charisma. It’s all about the sustained commitment of public resources and collective talent between the state and the private sector.

It’s a common criticism that such a policy is wasteful; it often backs the wrong technologies and industries. That’s true. However, the Silicon Valley model is also prone to periodic market euphoria, mania, panic and crashes, from the dotcom implosion to the current ongoing crypto-crashes. I will leave it to economic historians and econometricians to determine whether the state or non-state model is more wasteful or destructive.

Conclusions

Belatedly, the Biden administration is slowly realising that whether it’s containment against China or competition with it, the horse has bolted out of the barn already. That is why despite its hostile rhetoric, it has no coherent policy on how to deter or delay China’s technological drive for mastery or supremacy. This conflict cuts to the very ideological self-beliefs of the two countries. Only time will tell how it will turn out.

However, restricting or banning technological transfer will not work. The great British historian Arnold Toynbee famously wrote that it was usually countries or civilisations confronted with great or even mortal challenges that prevailed and prospered in history, not those that were well-endowed with rich resources. Denying China access to vital technologies at this late stage will simply force it to develop its own domestic capabilities. That won’t make it weaker, only stronger and more self-reliant.

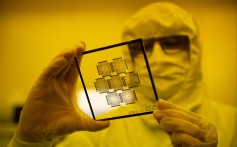

For years, American policymakers and pundits have believed China’s search for technological mastery or supremacy is doomed to fail or at least be consigned forever to mediocrity and also-ran status. This belief lies behind the strategy, first put forward by the Donald Trump administration, and now followed by Joe Biden’s White House, to restrict or ban the transfer of crucial technologies, notably the most advanced semiconductors and their production methods.

And yet, paradoxically, China is bound to succeed, despite the inevitable hiccups and setbacks, because it is essentially replicating the actual history of the economics and policies that led the United States to technological dominance, rather than the ideological history of what many Americans believe lies behind their success.

The Silicon Valley folklore is that of a lone maverick who has a great idea and pushes it to fruition, and in the process, creates a multibillion-dollar industry. That cannot be further from the assumption behind Japanese-Korean-Chinese state industrial policy, according to which innovation is a collective enterprise, not one of individual genius or charisma. It’s all about the sustained commitment of public resources and collective talent between the state and the private sector.

It’s a common criticism that such a policy is wasteful; it often backs the wrong technologies and industries. That’s true. However, the Silicon Valley model is also prone to periodic market euphoria, mania, panic and crashes, from the dotcom implosion to the current ongoing crypto-crashes. I will leave it to economic historians and econometricians to determine whether the state or non-state model is more wasteful or destructive.

Conclusions

Belatedly, the Biden administration is slowly realising that whether it’s containment against China or competition with it, the horse has bolted out of the barn already. That is why despite its hostile rhetoric, it has no coherent policy on how to deter or delay China’s technological drive for mastery or supremacy. This conflict cuts to the very ideological self-beliefs of the two countries. Only time will tell how it will turn out.

However, restricting or banning technological transfer will not work. The great British historian Arnold Toynbee famously wrote that it was usually countries or civilisations confronted with great or even mortal challenges that prevailed and prospered in history, not those that were well-endowed with rich resources. Denying China access to vital technologies at this late stage will simply force it to develop its own domestic capabilities. That won’t make it weaker, only stronger and more self-reliant.

For years, American policymakers and pundits have believed China’s search for technological mastery or supremacy is doomed to fail or at least be consigned forever to mediocrity and also-ran status. This belief lies behind the strategy, first put forward by the Donald Trump administration, and now followed by Joe Biden’s White House, to restrict or ban the transfer of crucial technologies, notably the most advanced semiconductors and their production methods.

And yet, paradoxically, China is bound to succeed, despite the inevitable hiccups and setbacks, because it is essentially replicating the actual history of the economics and policies that led the United States to technological dominance, rather than the ideological history of what many Americans believe lies behind their success.

They have applied their own ideological models to predict China’s supposedly “inevitable” failure, instead of using their own actual history of American technology and science, and economic policy, to analyse China’s development and acquisition of key technologies in the 21st century.

US cannot stop China's hi-tech rise | South China Morning Post

Alex Lo has been a Post columnist since 2012, covering major issues affecting Hong Kong and the rest of China. A journalist for 25 years, he has worked for various publications in Hong Kong and Toronto as a news reporter and editor. He has also lectured in journalism at the University of Hong Kong.

Related posts: